AI Governance, South Korea's AI Basic Act and SKT's T.H.E. AI: What the Future of AI Looks Like

As AI systems make decisions on loans, hiring, and healthcare, accountability becomes increasingly unclear. Korea’s AI Basic Act seeks to address this gap, but the industry is largely unprepared. This article explains why responsibility in AI must be deliberately designed, not assumed.

Prologue: Who Takes Responsibility for AI?

You've been denied a loan that AI recommended. The reason? "The system determined it that way." The AI doesn't explain why it rejected you. The bank employee doesn't know either. The developer only says, "That's what the model learned."

Whose responsibility is it? The AI's? The bank's? The developer's? The data provider's? If we can't answer this question, AI—no matter how smart it gets—cannot become societal infrastructure. Technologies that aren't trusted eventually disappear. AI governance is precisely the attempt to fill this "accountability vacuum."

In two weeks, on January 22, 2026, South Korea will implement its AI Basic Act. The law has been created. But is anyone ready? There are pioneering cases like SK Telecom's T.H.E. AI. The problem is that this is an exceptional case. Most companies, especially startups, have only a vague understanding of what governance even means. The law goes into effect in two weeks, but the field isn't prepared. Let's examine what AI governance is, what Korea's law demands, and how wide the gap is between law and reality.

Governance Isn't Control: It's an Accountability Structure

AI governance is easy to misunderstand. It sounds like "regulating AI" or "limiting AI development." But the essence is different. AI governance isn't about "how to build AI" but about "who will take responsibility for AI outcomes, and by what standards."

Consider these scenarios. What if a self-driving car causes an accident? What if a medical AI misdiagnoses? What if a hiring AI discriminates by gender? The problem isn't the technology itself—it's that there's no one to hold accountable. In traditional systems, it was simple. If a doctor misdiagnoses, the doctor is responsible. If a banker makes a bad loan, the bank is responsible. But when AI gets involved, the chain of accountability breaks. "The AI decided that way," "We just provided the model," "Maybe it's a training data issue"—responsibility evaporates between these responses.

Governance reconnects this broken chain. It makes everything traceable: who designed it, what data trained it, what criteria it uses for decisions, whether appeals are possible. The World Bank's report from last year defines this as "the core of AI trustworthiness is accountability traceability."

Global AI governance has rapidly crystallized over the past two years. The European Union began implementing the AI Act in 2024, strictly controlling high-risk AI through risk-based regulation. The U.S. announced its AI Action Plan last year, prioritizing innovation over regulation. China mandated AI-generated content labeling in March of last year, strengthening state-centered control. According to the Stanford AI Index 2025, AI-related incidents are growing exponentially each year. Bias, malfunction, privacy violations, misinformation generation have become routine. AI without governance is a ticking time bomb.

Korea's AI Basic Act: Principles Established, Reality Still Distant

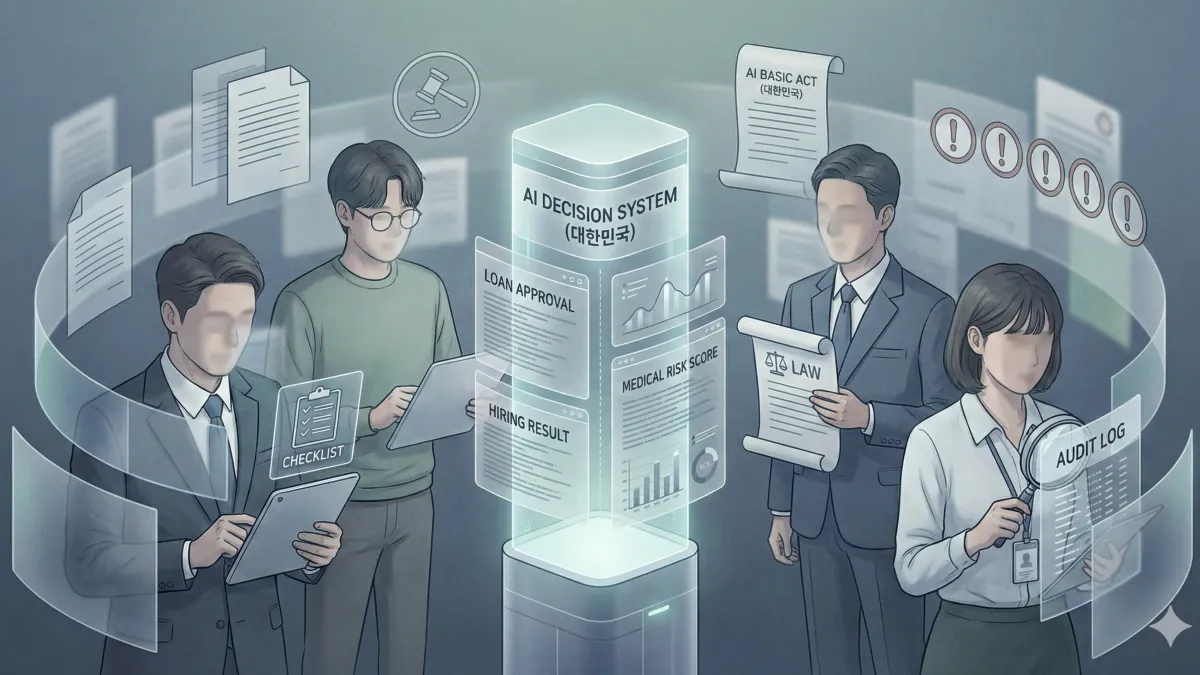

On December 26 of last year, Korea's National Assembly passed the "Framework Act on Artificial Intelligence Development and Trust Foundation". It was promulgated on January 21 of this year and goes into effect in two weeks, on January 22. The core of Korea's AI Basic Act isn't "prohibition" but "structure." Unlike the EU AI Act, it doesn't create a list of "these AIs are banned." Instead, it focuses on high-impact AI, requiring operators to identify risks, ensure human intervention, maintain transparency and records, and design user protection—operational obligations, not bans.

The law defines "high-impact AI" as AI that "significantly affects human life, physical safety, and fundamental rights." Specifically, this includes medical devices and digital medical devices, energy and water supply, transportation facility operations, evaluations of personal rights relationships like hiring and loan screening, public service qualification verification and decision-making, and student evaluation. Operators using AI in these areas have obligations to ensure transparency, ensure safety, and conduct AI impact assessments. Even foreign companies must designate domestic representatives.

The problem is specificity. The law says "ensure transparency" and "guarantee safety." But exactly what must be done, and how, remains vague. The government operates a grace period of more than one year after the law takes effect, during which no fines will be imposed. Legal obligations arise in two weeks, but actual fines won't start until next year at the earliest. The grace period sounds generous, but honestly, it means "neither the government nor companies really know what to do yet."

Is AI governance being deeply discussed in Korea right now? No. "AI ethics" gets mentioned at industry seminars, but most discussions remain abstract rhetoric. There are plenty of slogans like "We build responsible AI," but concrete answers like "We design responsibility through these processes" are rare. The law goes into effect, but the field's readiness is low. This gap is the problem.

SKT's T.H.E. AI: A Pioneering Attempt, But an Exception

SK Telecom (SKT) was the first Korean company to operationalize AI governance as a system. In March of last year, they announced the T.H.E. AI principles. In July of last year, they obtained ISO/IEC 42001 certification, the first among Korean telecom companies. In October of last year, they incorporated AI conduct guidelines into company regulations and had all members sign pledges. In September of last year, they opened the AI Governance Portal.

T.H.E. AI stands for "by Telco, for Humanity, with Ethics." Six principles lead to four verification areas, which materialize into over 60 checklists, completed by second-stage Red Team verification—an executable system. SKT structured T.H.E. AI into three pillars and six principles. The Telco pillar includes Connection and Reliability. The Humanity pillar includes Diversity & Inclusion and Human Welfare Enhancement. The Ethics pillar includes Decision Transparency and Ethical Accountability.

These six principles aren't abstract declarations. Each principle connects to specific codes of conduct and checklists. The AI Governance Portal operates through three stages: Stage 1 self-diagnosis, Stage 2 expert diagnosis (Red Team), Stage 3 lifecycle management. AI services go through multiple verification stages before launch. If problems arise, evidence that "we went through these processes" remains in the portal.

This is positive. But let's be honest. SKT is an exceptional case. It's a large corporation with resources, specialized personnel, and collaborative relationships with the government. Most companies can't do this. What about small and medium-sized enterprises? What about startups? Do they have staff to check over 60 items? Budgets to form Red Teams? Technical capacity to build AI governance portals?

SKT's T.H.E. AI demonstrates the possibility of "this can be done." But it's not a realistic solution for "everyone must do this." Rather, this case reveals the imbalance in Korea's AI industry. Large corporations can prepare. What about the rest? The law takes effect in two weeks, but most companies haven't even reached the starting line.

The Field's Disconnect: What's the Problem?

First, the guidelines are abstract. The government demands "ensuring transparency," "guaranteeing safety," and "impact assessment." But what specifically must be done, and how, isn't clear. Should companies create 60 checklists like SKT? Or are 10 enough? How many people should be on a Red Team? Is self-diagnosis sufficient? The law presents principles, but there's no execution manual.

Second, there's the cost and resource problem. AI governance isn't free. Creating checklists, designing processes, hiring experts, building systems—all require money and time. Large corporations can afford it. But what about an AI startup with 10 employees? Already under financial pressure, governance building feels like a luxury.

Third, social discussion is insufficient. The AI Basic Act passed, but no public forum has formed to discuss what this law means or what changes it will bring. Industry experts discuss it among themselves, but ordinary citizens don't even know the law exists. The media reported "AI Basic Act passed," but in-depth analysis since then has been rare. There's no social consensus on why AI governance is needed or what impact it will have.

Fourth, enforcement and oversight are ambiguous. After the one-year grace period, fines will supposedly be imposed. But by whom, by what standards, and how will oversight work? Even which government agency is unclear. The Ministry of Science and ICT? The Personal Information Protection Commission? The Fair Trade Commission? Who determines whether something is high-impact AI? Can self-assessment be trusted? When the enforcement system is unclear, laws remain declarations.

What AI Governance Changes, and What Must Be Changed

AI governance changes three things. First, legal change. Responsibility shifts from "technical debate" to "process evidence." When an AI incident occurs, the first question is "Did the company fulfill reasonable management obligations?" If there's prior assessment, verification, and logs, responsibility can be mitigated. Without them, the possibility of acknowledging negligence increases.

Second, philosophical change. As AI becomes smarter, human responsibility must become clearer. AI produces results that look like judgments, but philosophically, "judgment" is an act that can present grounds. The problem is that as AI advances, "why that conclusion was reached" becomes more obscure. Governance intervenes here. AI governance isn't about injecting morality into AI—it's a structure that prevents human organizations using AI from evading responsibility.

Third, social change. Trust shifts from "branding" to "operational capability." Not declarations like "We build ethical AI," but proof that "We have these processes." When models like T.H.E. AI emerge where "the seat of responsibility" is visible, questions from users, media, and regulators also change.

But reality isn't operating this way. Things must change. The government must provide concrete guidelines. What "ensuring transparency" means, what the minimum standards are, stage-by-stage checklists must be published. Reference the SKT case, but create a lightweight version executable by small and medium enterprises and startups. Cost support is needed. Tax benefits or subsidies for AI governance implementation should be provided. Social discussion must expand. A public forum on why AI governance is needed and what impact it will have must be created.

Epilogue: Responsibility Must Be Designed, But We're Still Designing

Back to the opening. You've been denied an AI-recommended loan. You ask why. In two weeks, legally, there will be an "obligation to explain the reason" to you. But in reality? You'll probably still hear "The system determined it that way." Why? Because while the law takes effect, the field isn't ready.

AI has already penetrated deep into our lives. In hiring, loans, healthcare, education, transportation—few areas remain without AI involvement. But without an accountability structure? Only distrust accumulates. Distrust leads to stronger regulation, and stronger regulation stifles innovation. AI governance can break this vicious cycle. But right now, we're still designing it.

Korea's AI Basic Act presented principles. SKT's T.H.E. AI created one positive case. But is this enough? No. Most companies remain in an ambiguous state. Government guidelines are abstract. Social discussion is insufficient. In two weeks, Korea's AI industry enters a new phase. But only a minority of companies have reached the starting line.

Only facts and balanced stories survive. Right now, Korea's AI governance has lost its balance between law and reality. The law moved ahead, but the field fell behind. Closing this gap—that's the biggest challenge for Korea's AI industry in 2026. Only responsible AI survives. And responsibility doesn't arise spontaneously. It must be designed. But still, we're in the middle of design.